When you hear “MVP,” your brain probably jumps straight to “Minimum Viable Product” faster than a startup founder pivots after a failed launch. But what if I told you there’s a better way to think about those three magical letters that could actually make your product succeed? Spoiler alert: it involves swapping one little word that makes all the difference.

The Origin Story: Where MVP Really Came From

Let’s start with a quick history lesson that won’t put you to sleep. The term “Minimum Viable Product” wasn’t born in a Silicon Valley garage or scribbled on a napkin during a late-night coding session. Frank Robinson coined it way back in 2001, long before everyone and their grandmother had a startup idea. Steve Blank and Eric Ries later popularized the concept, turning it into the startup gospel we know today.

Robinson’s original definition was pretty smart: “the version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort”. Notice something? Even back then, it was supposed to be about learning from customers, not just shipping something that technically works.

Fast forward to today, and MVP has become so mainstream that every product manager, startup founder, and their pet goldfish knows what it means. We’ve got pyramid diagrams, Venn diagrams, and enough blog posts about MVP to fill a small library.

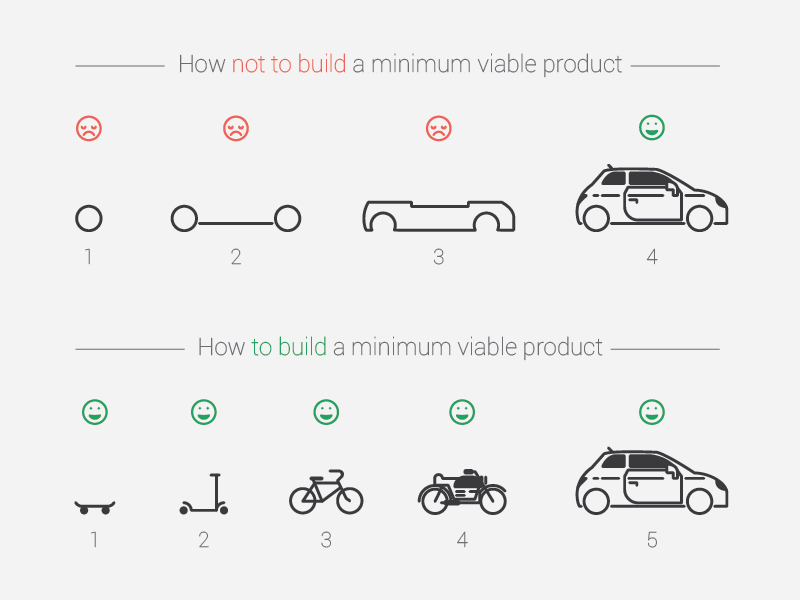

I plead guilty to over-using the following image when working with entrepreneurs.

Enter Ash Maurya: The Plot Twist I Didn’t See Coming

Just when I thought I had MVP figured out, along comes Ash Maurya to shake things up. If you don’t know Ash, he’s the brilliant mind behind “Running Lean” and “Scaling Lean,” plus the creator of the Lean Canvas – basically, he knows a thing or two about building products that don’t suck.

In a recent insight that caught my attention, Ash suggested something that made me do a double-take: what if we stopped calling it “Minimum Viable Product” and started thinking about “Minimum Valuable Product” instead? Yes!

Here’s his take: “An MVP (Minimum Valuable Product) is about nailing your UVP (Unique Value Proposition) with the smallest possible solution. Where ‘valuable’ isn’t limited to viability but also addresses desirability, feasibility, and other non-negotiable x-factors critical to your mission, vision, and values”.

Why “Viable” Is Actually Pretty Selfish

Think about it for a second. When we say “viable,” what are we really talking about? We’re essentially asking, “Can this thing survive?” It’s like asking if your houseplant will make it through the winter – purely about existence, not about whether it brings joy to your living room.

The problem with “viable” is that it’s company-centric. It screams internal metrics: “Is this technically feasible for us to build? Can we make money from it? Will our stakeholders be happy?” There’s nothing inherently wrong with these questions, but they’re all about us, not about the people we’re supposedly serving.

This inward focus explains why so many MVPs feel like apologetic half-products. Founders create something that meets their definition of “viable” – it works, it’s technically sound, maybe it even makes a few bucks – but users are left scratching their heads wondering why they should care.

”Valuable” Puts Users Where They Belong: Front and Center

Now let’s talk about “valuable.” When you say you’re building something valuable, you can’t help but ask the next logical question: valuable to whom? And unless you’re building a product exclusively for yourself (hello, dogfooding!), the answer better be “valuable to our users.”

This simple word swap forces a fundamental shift in perspective. Instead of asking “Will this work?” you start asking “Will this matter?” Instead of “Can we build it?” you ask “Should we build it?” It’s the difference between creating a product that exists and creating a product that people actually want to use.

Maurya’s expanded framework makes this even clearer. A Minimum Valuable Product doesn’t just check the viability box, it creates, delivers, and captures monetizable value while addressing desirability, viability, and feasibility. It causes people to switch from their old way of doing things to your new way, all while minimizing time, scope, and spend.

The Real-World Difference This Makes

Let me paint you a picture of how this plays out in practice. The “viable” approach might lead you to build a task management app that technically works, users can create tasks, mark them complete, maybe even organize them into lists. Boom, viable! It does what task management apps do.

The “valuable” approach asks different questions: What makes people’s lives genuinely better? What problem are we really solving? Maybe you discover that people don’t need another way to create tasks, they need help actually completing them. So instead of building yet another to-do list app, you create something that understands context, suggests optimal timing, or gamifies progress in a meaningful way.

This isn’t just semantic gymnastics. Companies like Zappos understood this instinctively. Their MVP wasn’t about building the most viable shoe e-commerce platform, it was about testing whether people would find it valuable to buy shoes online without trying them on first. They started by literally going to local shoe stores, photographing inventory, and manually fulfilling orders. Not particularly “viable” from a business operations standpoint, but incredibly valuable for learning what customers actually wanted.

Making the Switch: From Viable to Valuable

So what does this mean for those of us building products in the real world? It means every time you’re tempted to ask “Is this viable?” you should catch yourself and ask “Is this valuable?” instead.

When you’re prioritizing features for your next release, don’t just think about what’s technically feasible or financially sustainable (though those matter too). Think about what will genuinely improve someone’s day, solve a real problem, or make something difficult feel easy.

This shift doesn’t mean throwing business considerations out the window. Valuable products can and should be profitable. But it means starting with value and working backward to viability, rather than the other way around.

Conclusion: Three Letters, One Big Difference

MVP will always be MVP in terms of acronym real estate, but what those letters stand for in your mind can make or break your product. “Viable” might get you to market, but “valuable” gets you customers who stick around, tell their friends, and actually use what you’ve built.

The next time you’re sketching out your MVP strategy, remember Ash Maurya’s insight: it’s not just about building something that works – it’s about building something that matters. Because in a world where every problem seems to have seventeen different app solutions, the products that win aren’t just the ones that are viable.

They’re the ones that are valuable.

From now on, I’m definitely thinking “Valuable” alongside “Viable” – and definitely letting “Valuable” take the driver’s seat.